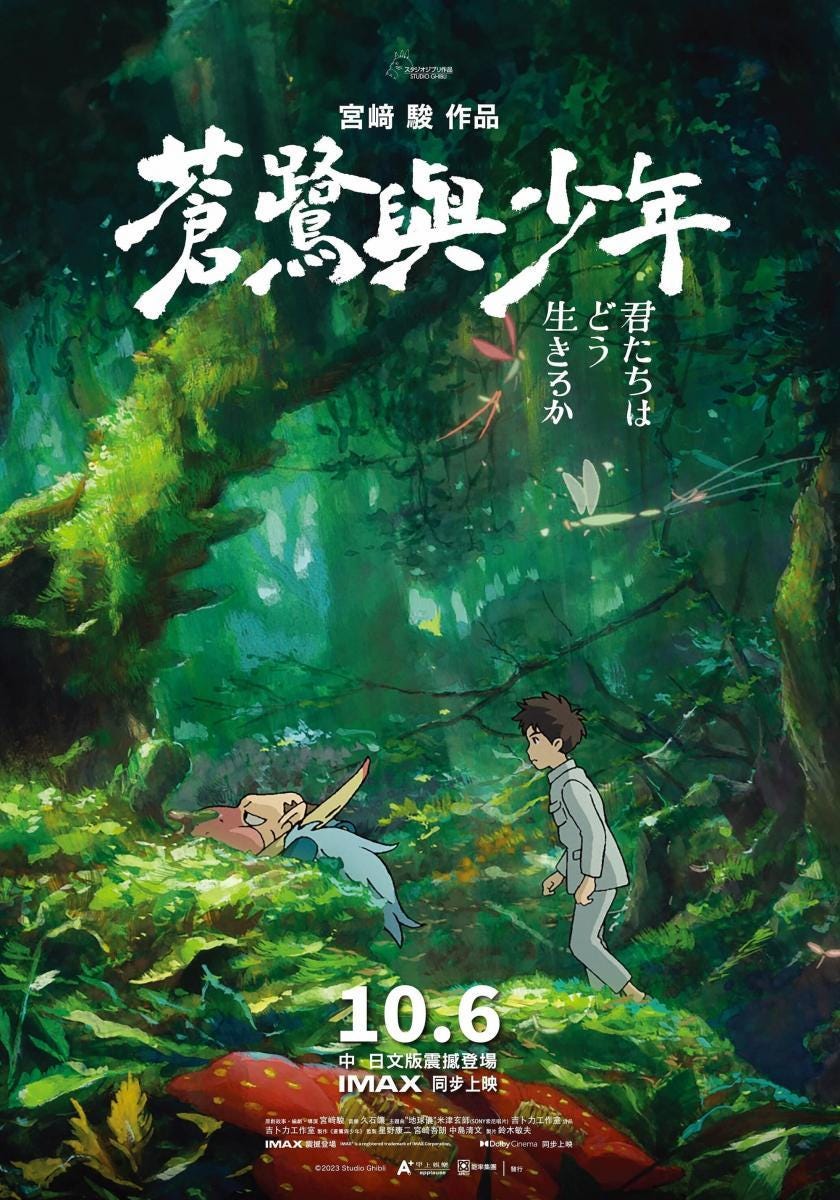

1. The Boy and the Heron

Directed by Hayao Miyazaki

Year: 2023

Language: Japanese (Original title: 君たちはどう生きるか)

Shaun’s Score: 3.3/5 ★

Before Watching:

Martin Scorsese once said “the most personal is the most creative.”1 I think that’s highly debatable—do I even need to spell out whom I’m subtweeting?2—but for Golden Bear holder and Academy Award-winning animation titan Hayao Miyazaki, The Boy and the Heron is perhaps his most personal feature to date. The protagonist Mahito struggles with the trauma of a Tokyo in flames and particularly his mother’s death, just as Miyazaki recounts war-torn Japan as the setting for much of his own earliest memories. Thus, the film sings of the wonder and imagination from Miyazaki’s youth, and oh boy, (hark) the Heron angels sing.

Mahito (Soma Santoki/Luca Padovan in the English version) relocates to the countryside with his father3 after the hospital fire that claims his mother’s life. Following all tropes of displaced wartime youth (*cough* The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe? *cough* Peter Pan?), Mahito is unhappy in his palatial, bucolic hideout, guarded by his aunt-become-stepmother Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura/Gemma Chan) and a veritable army of grannies on staff. The curious estate is also home to an insolent, titular gray heron (Masaki Suda/Robert Pattinson[!]) which eventually entreats our young hero to embark on a realm-hopping adventure. This secondary world employs all the Ghibli little horses, like a gritty local ally (Kô Shibasaki/Florence Pugh) and a skilled warrior-magician (Aimyon/Karen Fukuhara), alongside delicious albeit 2-D food and gazillions of little fluff balls (the “Warawara”). Mahito must meet the challenges of the tower wizard helming this universe before his stepmother (and everything else, I guess) spirits away.

Even mediocre Ghibli outpaces top-notch American animation, but this film is not without its faults—primarily in world and narrative construction. Miyazaki is best when his immense imagination remains focused, as was the case in Spirited Away (2001) and Howl’s Moving Castle (2005). The Boy and the Heron, by contrast, spills into a scattered world that is difficult to connect while also recycling lots of plot structure. Look, I understand: Miyazaki is 82, and this was (literally) the most expensive film ever produced in Japan. Its release has been delayed and delayed, and it’s difficult to keep an octogenarian on task. But serendipitously, the film’s sprawl ends up being both its downfall and the core of its charm: Miyazaki’s vision of human resilience to loss is far grander than any of us can synthesize in one setting. That is the good news, and that is the bad news. And now, he has (for as little as it’s worth) a Golden Globe to show for it.

The Boy and the Heron premiered at the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival, and is now available in theaters worldwide.

After Watching:

While I usually avoid dubs like an Alaska Airlines window seat, I’m actually intrigued to see this English version. Other anglophonic castmates include Christian Bale, Mark Hamill, Willem Dafoe, and Dave Bautista (oh my).

Miyazaki often finds surrealist, childlike fantasies to digest displacement, but The Boy and the Heron is even more unbounded and free-form than usual, the loss all the more inescapable by traditional means. We see this in the film’s Japanese title, which translates to “How Do You Live?”, as is also the name of the book that Minato finds with his mother’s inscription. Miyazaki seems to wonder how we all live in the face of omnipresent tragedy, but in having Mahito climb the Stairway to Heron and traverse a world seemingly dictated by a game of Jenga just for family, he proposes an answer: alongside the loved ones still with us. Anyhow, it’s definitely a win for the “birds aren’t real” subculture.

2. Evil Does Not Exist

Directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi

Year: 2023

Language: Japanese (Original title: 悪は存在しない)

Shaun’s Score: 3.8/5 ★

Before Watching:

I’ll be the first to admit that I am criminally predisposed to enjoy Hamaguchi. I’m talking Obama-picking-his-own-movies level bias, as Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy and Oscar-winner Drive My Car were my 5th and 1st favorite films of 2021, respectively. His cinematic experiences are so sensory, so engrossing, so resonant; not to mention he manages to portray quotidian car ride dialogue with the intrigue of a White Lotus season finale. And in a normal year, if you had told me that both Kore-eda and Hamaguchi would be releasing dramas in the same festival cycle and that I’d prefer Kore-eda’s, I would have spat in your face (jk, I’m not Maïwenn). Yet despite falling short of his (admittedly, insurmountable) 2021 achievements, Ryusuke Hamaguchi still pulls off a subtle eco-thriller in Evil Does Not Exist.

The story tracks the remote village of Harasawa after a proposal arrives for the construction of a glamping site. And no, our villain is not a voracious Gwyneth Paltrow, but can you just imagine her redirecting her court-core and yonic candle kingpin energy to gentrifying rural Japan? Now that is a remake of Bullet Train that I could sit through. Anyway, the site could allegedly bring tourists from Tokyo to the countryside, but a stand-off ensues between the glamping site’s obdurate private equity backers and the environmentally concerned people of Harasawa. Trapped as the go-betweens are two talent agency functionaries, sent to run a glamping facility Q&A when they encounter unexpectedly passionate resistance; luckily, Hamaguchi is the only director I know that can make a panel discussion on septic systems feel as biting as Suits. One such vocal citizen is Takumi (Hitoshi Omika)—a jack-of-all-trades handyman, woodchopper, and occasionally distracted single father. What first seems like a cut (chopped?)-and-dry tale about a community railing against corporate greed unexpectedly morphs into something totally different.

Evil Does Not Exist is both a textural and textual departure from Hamaguchi’s signature styles. His previous narratives have typically been either free-wheeling (like Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy or Happy Hour) or breathlessly crisp (as Drive My Car), and their messaging has always been declarative. For example, Hamaguchi’s adaptation of a searching, pained Murakami short story into Drive My Car brings a more definitive resolution to the source material than Lee Chang-dong’s Murakami adaptation Burning. Evil Does Not Exist, however, drifts from this mold: in form, it’s somewhere in between his free-wheeling and his crisp styles, and in message, its conclusion is far more question than answer. Leaving the theater with a complete picture will likely require some prayer—in the name of the father, son, and House of (Hama)guchi.

Evil Does Not Exist premiered at the 80th Venice International Film Festival, where it nabbed the Grand Jury Prize and the FIPRESCI Award, before also securing the Best Film award at the 2023 London Film Festival. It is now available in select theaters worldwide.

After Watching:

Why does Takumi snap? Hamaguchi inverts the sense of bucolic peace curated by the first ¾ of the film, leaving us wondering “hey, does evil exist or are we all just running on animal instinct fumes?” Unfortunately, this finale is a lot to chew on (Hamaguchi himself admits he loves “being puzzled”), and the dialogue of a small town caught in between development and preservation gets washed away. Still, I’m a sucker for anything with a climate angle, and I could watch Hitoshi Omika chop wood for another five hours (eat your heart out, Happy Hour4).

Bong Joon-ho cited this quote in his Best Director acceptance speech at the Academy Awards, where he actually bested Scorsese.

Sub… -X-ing?

Mahito’s father produces fighter planes, just like Hayao Miyazaki’s own father did in World War II.

Runtime: 5 hours 17 minutes.